In 2016 we have instant fact-checking, pundit commentary, and a constant stream of information (and misinformation) defining the parameters of our political debates. As our culture continues to adjust to being an information-rich society, what might debates look like in the future? And what happens when information technology reaches equilibrium across the globe, when billions of people have the information they need to institute change?

My recent novel Infomocracy envisions a system of global micro-democracy where multiple parties, each with vastly different platforms, compete for votes among citizens scattered across the globe. These citizens vote in groups of one hundred thousand people called “centenals,” making elections in this near-future world a thrilling high-stakes race to connect with voters with different concerns, different languages, and different views of what government should be. Debates can involve dozens of parties, and they’re a crucial chance to put forth a message that resonates across this wide and complex scope.

Below, a world watches the latest presidential debate.

Chapter 7

ANNOUNCER: Welcome to the first debate for the third global election! We welcome representatives of the thirty-three governments that meet the official cutoff to be candidates for the Supermajority position, according to the latest round of official Information polling. Each of the candidates will now present a brief opening statement, followed by questions from the moderators.

HERITAGE: Thank you, and we are very pleased to participate for a third time in this inspiring and historic process of global democracy! We are also thrilled to celebrate with you, with our constituents all over the world, and with everyone who is participating in this wonderful exercise of citizenship and empowerment! You are the ones who make micro-democracy great—we couldn’t do it without you! And so, before we even begin, I want to thank you for giving us the opportunity not only to govern our centenals but also to guide this amazing effort toward peace and prosperity as the Supermajority for the past twenty years!

Ken shakes his head and takes another swig of his beer. William Pressman is so smug and obnoxious. If he were on the Heritage team—not that he ever would be!—he’d advise them to cool it with that. He doesn’t think their attitude helps them with undecideds. Although considering their record, he could be wrong about that.

Despite the unpleasant ambiance at the Policy1st office, he stayed in Jakarta to watch the debate. He’s managed to find a centenal where alcohol and marijuana are legal but tobacco and pop-out advertisements are not. As Ken waited for the debate to start, he checked out this government’s broader policies. They’re called Free2B, which sounds like they might promulgate that kind of individualism that gets annoying quickly once your neighbor starts playing gronkytonk at top volume at five a.m. or refuses to donate to the volunteer fire department until their house is burning down, but when he scans their policies, he sees they’re reasonably socially conscious. If they’ve got anything in a more temperate climate, he’s seriously considering moving there once the election is over.

Despite the unpleasant ambiance at the Policy1st office, he stayed in Jakarta to watch the debate. He’s managed to find a centenal where alcohol and marijuana are legal but tobacco and pop-out advertisements are not. As Ken waited for the debate to start, he checked out this government’s broader policies. They’re called Free2B, which sounds like they might promulgate that kind of individualism that gets annoying quickly once your neighbor starts playing gronkytonk at top volume at five a.m. or refuses to donate to the volunteer fire department until their house is burning down, but when he scans their policies, he sees they’re reasonably socially conscious. If they’ve got anything in a more temperate climate, he’s seriously considering moving there once the election is over.

The bar is unfinished blond wood with light fixtures made of old-fashioned glass beer bottles and lots of ceiling fans powered, according to a sign in the bathroom, by an anaerobic reactor. They have a wide range of drink and drug offerings and some good early ’20s music playing through the ambience. It’s too bad he has to get on a plane tomorrow; there’s a World Cup elimination match he wants to see, Hokkaido versus Greater Bolivia, and this would be a great place to watch it.

The Heritage spokesperson is complaining about why there are thirty-three governments included in the debate. Since Policy1st is currently thirteenth in Information’s ranking of Supermajority candidates, Ken would very much like for there to be exactly thirteen parties up there. Or maybe fourteen or fifteen, so his isn’t dead last. Thirty-three does seem like a lot—even with simulquestions, this is going to take forever. But Heritage wants to cut it down to five. Naturally, the fewer governments people take seriously, the better chance Heritage has to hold on to what they’ve got. Having looked at the numbers recently, Ken knows that the text and animations that the moderator is superimposing over Heritage’s long-winded statement are accurate: there’s a huge gulf between number thirty-three and number thirty-four on the list, so it’s the most sensible place to make the cut.

Whether the ranking criteria are valid is a whole separate set of questions, though, and one that no one but the big muckamucks at Information is likely to get a chance to ask.

HERITAGE: You will see many advids from our opponents, and particularly from Information, claiming that we have not kept every single one of our campaign promises. But we would like to remind you that, as the only Supermajority holder in history, we are the only ones who have been tested in this way. It is easy for the others to claim they will keep all their promises if elected.

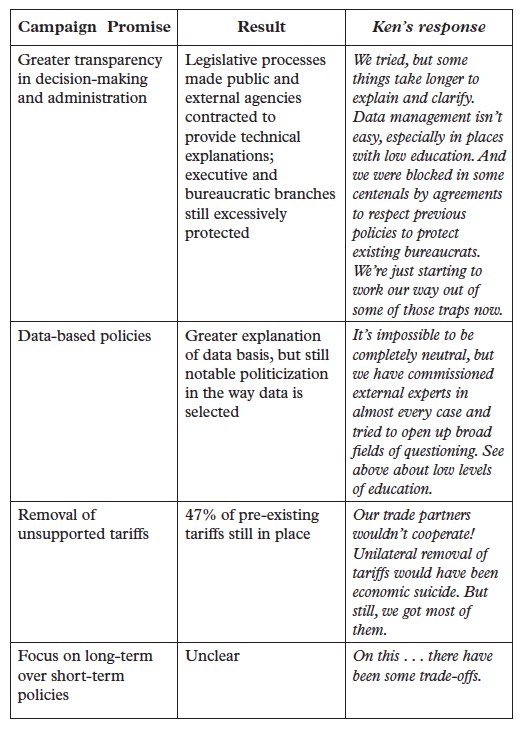

This argument makes Ken grind his teeth. Dodgy as it is for Heritage to admit they haven’t kept all their campaign promises—in fact, he thinks, they’ve barely kept any—this is a very clever way for them to do it. All of the governments on that platform have several thousand centenals and therefore plenty of data about how well they’ve held to campaign promises, even if not as the Supermajority. By accusing the reliable scapegoat Information of bias, Heritage can defend itself and point out the failings of its competitors at the same time. Indeed, as Ken watches, some jerk at Information takes the bait and starts scrolling down the screen a table with all the data they’ve accumulated on broken promises by other governments. Ken waits, trying not to cringe, until Policy1st’s turn and internally refutes every accusation:

Noticing that absinthe is also legal here, Ken decides to move on from beer.

LIBERTY: …and we welcome the chance to set forth our ideas for world government as we celebrate another decade of freedom and economic growth in our centenals!

Yoriko finds herself nodding along with the people around her. She is watching the debate at a Liberty campaign event: a huge projection set up on the beach, with cows turning on spits and, of course, lots of free Coke and Dasani, Gauloises cigarettes, Degree antiperspirant and Unilever soap, and Nestlé breast-milk substitute. There’s a play area set up for small children, which Yoriko appreciates (she couldn’t get a sitter) almost as much as she is surprised by it. She thinks of Liberty as being uncaring and not exactly family-oriented.

STARLIGHT: We’d also like to protest the refusal of Information to broadcast vid as well as sound. We feel that the public has the right to see as well as hear their candidates. Studies have shown that nonverbal language is a key element of trust and decision-making.

Mishima doesn’t move, but inside she’s somewhere between rolling her eyes and cursing. She can’t believe Star-Light is among the contenders, if toward the bottom of the pack, and she really can’t believe they’re dragging this argument out again. They better be out by the next debate. As she watches, whoever’s working the debate starts scrolling text down the screen about why debates are sound-only. It’s a stupid, process-oriented point to even be having a discussion about, but Mishima knows that all over the non-election world—in Saudi Arabia, in Switzerland, in holdouts of the former USA and PRC and USSR, people are watching the debate for its entertainment value and loving every dig at Information.

She can’t show her indignation, because having stayed an additional night at the Merita hotel, she’s watching the debate in the bar. She would prefer to be alone or with like-minded colleagues, but she considers it a professional responsibility to check reactions. The Merita has thrown an actual party for the debate, with reduced-price drinks and free snacks, and a lot of people have shown up. Unfortunately for Mishima’s purposes, more of them seem more interested in the drinks and snacks (and each other) than in the massive and multi-linked projection of the debate. Mishima can barely hear through all the meaningless chatter, and she has unobtrusively turned on her earpiece and linked it in to her own feed.

POLICY1ST: …we welcome the audio-only format of the debates, as well as the simulquestions and the comparison sheets. These elections should be about policy, not presentation, and not even people. Our government officials are all chosen for their qualifications and capacity, not for their looks.

Ken catches himself wincing, or maybe it’s the alcohol. Not that he disagrees; of course not. He just wishes Vera Kubugli hadn’t let herself get pulled into such a silly issue, and without excuse of a direct question. Something about it sounds smug and self-righteous, which is a bigger risk for Policy1st than for Heritage.

Still, he is guiltily glad that it’s Vera representing them in this debate, rather than Suzuki, who has an even greater tendency to let his tones get sententious. Vera is warmer, or at least comes across that way—Ken’s only met her briefly. Also, she’s female and not remotely white. Ken has gotten the sense that she’s one part of the government that Suzuki can’t micromanage.

Wow, absinthe really works fast. And well. Ken admires the empty cup, then punches in the order for another.

MODERATOR: Thank you all for your opening statements. We will now move on to the questions. As you all know, due to the high number of participants, we will be taking answers in groups simultaneously. The audience can select which voice to hear while the other answers are transcribed on the screen; we do encourage you, however, to listen to the recorded answers of all the respondents later, to get the full effect of all of their statements.

Mishima orders a bourbon, pleased that she is no longer in the Information trenches. When her drink comes, she raises a silent toast to all the grunts who are poised at their interfaces right now, fingertips and neurons twitching. There are two groups of Information workers on a debate: the A team, which does the simultaneous fact-checking and context-setting that viewers see on their screens, and a second set of less-senior but also well-regarded staffers who collect data

from the listeners and integrate it into analysis and projections. One of the first Information datasets to come out of a debate is which government got the most listeners. Some argue that it’s not a great determinant of the way the polls will move next, on the theory that people listen for entertainment value and vote out of self-interest, but Mishima has been with Information long enough to be cynical: most people’s interest is entertainment. From the icon in the corner of the big projection, she can see that this Merita hotel is tuning into Heritage, which now that she thinks about it, is not particularly surprising even if they are sitting in an 888 centenal. She brushes her hair back, casually adjusting the feed in her earpiece to listen to Liberty.

MODERATOR: Let’s move right into something that some of you have mentioned in your opening statements: law and order. Suppose that an individual commits a violent crime in the jurisdiction of some other government and then flees into one of your centenals. Will you extradite that individual, subject him or her to a judicial process under your government, or ignore this circumstance unless the crime affects your citizens?

In Addis Ababa, in the same bar where he met Domaine (what a nutter!), Shamus rolls his eyes. They always haul out this question, or something like it, for the debates. For all of Information’s bullshit about transparency and clarity and highlighting differences, they live off of people using their communications and reference systems, and they love questions that get people talking. Extradition policies are all clearly posted in the comparison sheets, but people still get excited about crime, even if there’s nothing new in the answers. He keeps an eye on the debate projection in the bar but switches his personal feed back to football replays, and curses Information again for not allowing any live matches during the debates.

HERITAGE: …in addition, we would like to take the opportunity to decry the incidents of violence that have been occurring in far too many centenals in the run-up to the election. It is deeply unfortunate that the micro-democratic process causes so much strife, and we earnestly hope that someday we will always be able to govern the way we do between elections: peacefully and prosperously.

Subtext: skip the elections and let us rule forever, Mishima thinks, slugging back the rest of her bourbon. It’s enough to make her wish she hadn’t shut down that WP=DICTADOR fire-writing in Buenos Aires quite so quickly. She orders another, willfully oblivious to the solicitous expressions on the faces of various high-paying guests hovering in her vicinity.

POLICY1ST: Our extradition agreements vary from government to government. We would never extradite someone to a government with cruel or unusual forms of punishment; however, we would likewise never let a violent criminal wander our centenals unpunished and unrestrained. So, while the precise answer will vary according to the case, you can be sure that such an individual would be subject to a process of justice, either under our laws or under those of the centenal where the crime was committed.

Ken nods, satisfied. He hopes that a lot of people were listening to Policy1st, because Vera nailed it: not only the words, but also the firm yet compassionate tone. As much as he agrees in principle with Information’s embargo on video during the campaign, he wishes people could see her open, earnest face as she’s speaking.

He listens to her on his earpiece, but with the volume low enough so that he can hear the soundtrack playing in the bar, too. They are taking votes among the patrons to decide which feed to listen to for each question (seriously, Ken loves this government—maybe it’s just the bar, but surely an enabling environment has something to do with their easy participatory approach) and so he hears a bit of PhilipMorris’s answer, which everyone wanted to listen to because they are famous for their continued defense of the death penalty. At the same time, he scans the transcribed answers crawling up the projection, with some extra attention to Liberty’s. Nothing surprising leaps out at him. Everyone knows the extradition policies anyway; this is a pure crowd-pleaser.

MODERATOR: Thank you. The next question is on foreign policy. Now, we are all aware of the legal issues concerning centenal sovereignty, but there are grey areas staked out by treaties and inter-centenal coordination, and cross-border concerns have raised new models of how centenals may interact. The question is: are there any circumstances under which you would attempt to influence a centenal belonging to another government?

In the bar in Jakarta, in the hotel in Singapore, and on the beach outside of Naha, Ken, Mishima, and Yoriko lean forward simultaneously. Ken switches his earpiece, then registers that he is hearing the same thing from both ears; the bar has voted to listen to Liberty. He wonders whether the rumors are out while loyally switching his own feed back to Policy1st; every listener helps build their buzz.

LIBERTY: Of course, we respect the integrity and political independence of all governments. We also respect the rights of our own citizens, their needs, economic fulfillment, and pursuit of happiness. And especially, of course, their freedoms. And we will defend that.

Mishima stands up, drains her third glass, and heads for her room, ignoring the gestures of the well-dressed man sitting next to her, who’s been trying to buy her a drink for half an hour. Ken slumps back in his chair and wishes he were more (or less) sober. Yoriko, sitting on the warm sand and listening to the warm voice of Johnny Fabré boom through excellent acoustics into the night around her, wishes suddenly and urgently to be somewhere else.

Domaine, still in Saudi, misses the debate entirely.

Excerpted from Infomocracy © Malka Older, 2016